Lately, a few articles about old v. new violins have been circulating. One, written by Daniel Wakin of the New York Times, has even made it onto my Facebook wall. (As far as I know, this article by Nicholas Wade is what set things off.) I have a lot of thoughts about this subject, but I'll begin with a brief history of my own violin experiences. My first full-size violin was a late 18th century Irish violin (I've forgotten the name of the maker.) As I got more serious about music while in high school, I switched to a 1925 Matthias Heinicke violin. Midway through my undergraduate years, I upgraded to an 1842 Thomas Kennedy violin, which I still own. I have always been loyal to whatever instrument was in my possession, and I rarely tried out other violins that I encountered in shops or in the hands of my peers. Whenever I did try another instrument, I would invariably dismiss it after a few notes as "not for me." I was used to my own instrument, comfortable with the feel and sound of it, and I didn't see any reason to try to get to know any other instrument. I was content with what I had--until a few experiences opened my eyes and my ears.  The first such experience was an audition for the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. I didn't win, and I requested feedback. Combing through the comments that I received, I was struck by one comment in particular: "Not a fan of this violin." This was not the first time that my Kennedy had been criticized, but it was the first time that someone had made explicit the fact that my instrument might be holding me back. My feelings toward my violin began to waver. The second eye (or ear) opening experience was much more positive. I was gifted with the use of a Stradivarius for one week, culminating in a lunch-time recital called "Strad For Lunch." (One might recall that this was also the impetus for this website!) This was my first time putting my hands on such an instrument, and I could immediately feel the difference. That's not to say that I immediately fell in love with it--the Strad was too different from anything I had previously played for me to really be comfortable with it. However, I could feel the depth and power of the old Italian instrument, and at the end of the week I reluctantly relinquished it. After this experience, I resolved to somehow "upgrade" to a better violin. The main obstacle was price. I don't have the 100k that a really good violin would cost, let alone the several million dollars that Strads generally go for. I concluded that the best value for my money would be a contemporary instrument. Ideally, I would sell my Kennedy and use that money towards a new instrument. In the real world, this is not as simple as it sounds. Violins typically spend a year or more in a shop, waiting to be sold on consignment. But what would I do while my violin was on display? With the backing of my teacher at Juilliard, I approached the curator of Juilliard's instrument collection. After some forms, signatures, and a few weeks of waiting, I was cleared to borrow an instrument from Juilliard. The school's instruments are stored in a small room, built like a safe. From this room, the curator brought out an instrument for me to try. It was a little big for my taste. He disappeared into the back room, and emerged with a second instrument. This instrument was--I kid you not--a little smaller than I expected. Patiently, he disappeared once more into the back room, and emerged with a third instrument. The instant I put my bow to the strings, I knew this was it. I told him that this instrument was perfect for me, and I asked what it was. It was a Nicolo Gagliano, from 1743. (Once upon a time, Gagliano violins were considered to be affordable alternatives to Stradivariuses and Guarneriuses. Alas, they are no longer affordable.) So it came to be that, in my quest for a contemporary violin, I wound up with an old Italian violin. An ironic layover, but my sights are still set on a 21st century instrument! Stay tuned for the second installment: New violins.

5 Comments

This has been a pretty crazy year for me: my debut in Carnegie Hall, a trip to Japan with the Met, a summer gig at Tanglewood, starting a new program at Juilliard, and of course my engagement to Nana! In retrospect, 2011 was awesome--how will 2012 be?

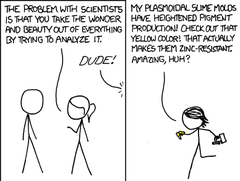

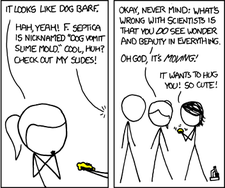

I sometimes look back at my younger self and yearn for the simplicity of a life where you do your best and things just worked out. Study hard, and you got good grades. You were guaranteed a bed and a roof, food was on the table every night, and somehow the car always started up in the morning. If you had some sort of failure, well, there was always next year. (I still vividly recall a "failure" at a youth orchestra audition. I sat tight for the year, practiced hard, and redeemed myself the next year.) The first time I felt that the world had the potential to be harsh was while applying to colleges--but even then, I was applying for 1 of approximately 20,000 openings across a half dozen schools. Today, I live in New York. I'm still in school, but I'm also doing whatever gigs I can get my hands on: teaching, performing, recording, and more. But every time I visit my family in California, I take a break from doing and thinking about these things. I don't think about rent, I don't have to buy groceries or make dinner, and one of the three family cars is usually available for use (gas included). Here in California, I have time to reflect on the past year, and on the 24 years before that. My prediction for 2012? It's going to be awesome.  What is musicology? In 1827, the Germans coined the term Musik-wissenschaft. It wasn't until the twentieth century that we English speakers came up with our own word to describe the scholarly study of music: musicology. Thus for a hundred years--and arguably extending to today--people have equated musicology with "music science".  I disagree with this definition for so many reasons that I'm already planning out another blog post. But for now, I'll go along with the popular view. Musicology is the science of music: Many people cringe at this thought. Science is intellectual, music is emotional. Can the two really get along? (Never mind that the Greeks put music in the quadrivium next to arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy; that's neither here nor there.) Doesn't analysis just take the wonder and beauty out of everything? Short answer: No, see above comic. I empathize with those who have sat (or slept) through boring analytical lectures, where the professor drones on and on about... actually, I'm drawing a blank because I don't stay awake through such lectures. This isn't musicology, this is just uninspired teaching. For me, musicology is a tool for discovery. Sometimes a discovery will affect how I perform a piece. Other times a discovery is just cool in and of itself. Maybe nobody will actually hear the palindrome in the tenor and bass of Josquin's Agnus Dei from Missa L'homme armé sexti toni. (Yes, I just wrote a paper comparing two Renaissance Masses.) But isn't it cool that it's there? Come on, it's at least as cool as "Dog Vomit slime mold". Two years ago, I wrote a paper about the interpretation of music. It was my senior project, the culmination of four years of studying music at Harvard. Along with submitting it to my adviser, I posted it on Facebook and emailed a copy to my mom. Yeah, I was proud of that paper. And now my views have changed.

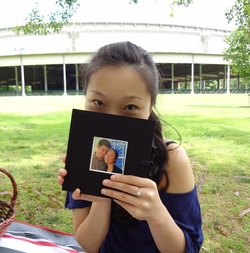

You can read it here if you want, though I don't necessarily recommend it. Summarized in a single sentence: The composer's intent is the ideal toward which we strive. An unspoken premise is that the composer is always right. I treated this premise as obvious, like the fact that heavier things fall faster than lighter things, and objects in motion tend to come to rest. Two years wiser, I no longer see this as self evident. Why should a composer always be right? A composition can only be transmitted through performance, and performance necessitates interpretation. Even a composer performing his own composition is (ideally) adjusting his performance based on the performance space, the audience, his own internal feelings at the moment, and probably numerous other factors. (After performing the Schumann Piano Quintet six times in four days, I no longer believe in a single ideal performance. Six ideal and identical performances would be torture.) Composition and performance are two distinct actions (except in improvisation.) In nearly every performance to which I listen, there are ideas that I agree with and ideas that I disagree with. When I like a performance, I probably agree with more ideas than I disagree with. When I dislike a performance, vice versa. I never agree entirely with a performance--assuming I'm actively listening--so why would I expect to agree entirely with a composer's performance, or his intent? That's not to say that I don't value the composer's ideas on performance. Knowing how the composer wants his piece performed is essential to interpreting with integrity. However, his word is not the last word. This idea is especially relevant when working with a living composer. Two years ago, I probably would have passed the buck on to the composer. If he wanted something that I disagreed with, well, I would do what he wanted and put the responsibility on him. These days I take a different approach. My goal as a performer is to convince the audience, and I have to be convinced myself if I am to do any convincing. Thus I strive to understand what the composer wants, not just blindly follow orders. Maybe it's time for a sequel to that paper. It happens like this: On the morning of our third anniversary, I took Nana out for a morning picnic on Tanglewood grounds. She was a little surprised that I was making such a big deal about our anniversary this year, but I managed to allay major suspicion by making up nerdy musical reasons about why the number 3 was so important. (Bach, the Holy Trinity, etc.) It was a cider, cheese, and crackers affair, as you can see here: Nana's look of shock is from apple cider foam bubbling out of the bottle after explosive decompression. She still has no idea what's coming up. For my non-Tanglewood friends, here's a panoramic view from our picnic: That building is the Shed, where the Boston Symphony Orchestra performs several times a week. On this Wednesday morning, however, it was actually the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra rehearsing Brahms's Second Symphony. A perfect backdrop for the event! Here is Nana's first surprise of the morning: a photo album! I had been secretly constructing this for the past two months, and she was happy to sit down with me and go through the album. And at the end of an album was a question. At that moment, TMCO just happens to start the second movement of the Brahms. I kid you not. Brahms Symphony No. 2, Adagio no troppo I had slightly overshot the size of the ring (it's HARD to guess a girl's ring size!) so Nana is wearing the ring on her middle finger for now. It didn't take long for word to spread through Tanglewood, thanks to a missed rehearsal (sorry, Adrienne!) and Lunch Club with all of TMC! Also Facebook. A week later, we got the keys to our new apartment in Astoria! If I learned one thing on my trip to Japan with the Met, it is the importance of time. As an opera orchestra, the Met orchestra deals with the issue of time to a much greater degree than does a typical symphony orchestra. An instrumental soloist will already be quite flexible with time, and a singer, dealing with text as well as music, will take even more time. Thus the Met orchestra is always prepared to pull back or rush ahead at the whim of the soloist. As a veteran musician explained to me, "We don't even think about this kind of stuff." Clearly there's some ESP going on. So what does the Met do when freed of their obligations to a singer? Why, take time! The symphonic repertoire on the Japan tour was Strauss's Don Juan and Til Eulenspiegel. Til is a piece with which I feel very familiar, as I've had a chance to perform it as both concertmaster and principal second. The Met, on the other hand, is not very familiar with Til, and it was very interesting for me to see them master it in about an hour. Most interesting to me was what Maestro Luisi didn't have to ask for, which is rubato. The maestro offered his input through the baton, of course. However, the end result felt guided, rather than led. In the introduction to Til, the orchestra chose to take a little more time than the maestro signaled (at least, that is how my literal eyes interpreted his gestures), and they did so with unity and conviction. I was sold. Rubato could have been my greatest enemy. The Met musicians were intimately familiar with La boheme, Don Carlo, and Lucia di Lammermoor, and thus no rehearsals for these operas were held on tour. I spent the first week on the edge of my seat for the entirety of each opera, not knowing when the pulse would speed up, slow down, or even come to a halt. Gradually, though, I began to feel the heartbeat of the music along with the rest of the orchestra. I recall clearly a moment in Don Carlo where an unwritten caesura took place--an abrupt stop in the music. I found myself frozen, without having consciously perceived the caesura. My heart began to hammer as I realized that I was standing at the edge of a cliff. One note too far, and my stray note would have rang throughout the hall. I breathed out as the music continued. I had passed. Opera!

I just arrived in Tokyo, joining the Met Opera Orchestra on their Japan tour. (I'm just as surprised as you are, trust me.) I'll be posting several times during my tent days here, as I experience for the first time a professional orchestra on tour. This will also be my first solo trip to Japan (discounting the 600 or so other musicians and crew members, of course.) This first post, however will not be about the experience, but about the music. As you might expect, my preparation for this gig involves not just practicing, but also listening to recordings and studying the score. During the long flight from San Francisco to Narita Airport, I settled down with Puccini's La Boheme. Since I've listened to this opera dozens of times, I knew what to expect. As Mimi and Rodolfo uttered their last words to one another, I stoicly followed along in the score. I reached the penultimate page, moved but still composed. I turn the page. "Coraggio!" shouts Marcello, and I am no longer composed. What? The music and the story themselves are tragic. Rodolfo's cries of "Mimi" are heartwrenching. For me, however, it is the single word Coraggio, not sung but spoken, that pushes me over the edge. Marcello's support emphasizes the collapse that follows, and it reminds me that this is not "just" art; this is life. Life is what art is all about. Coraggio is why Puccini, more than any other composer, moves me to tears. Miami in December is perfect. Miami in May is still beautiful, albeit with some humidity and lots of mosquitoes. Four mosquito bites and a sunburn are my mementos from my latest subbing experience with the New World Symphony.

While I'm clearly ambivalent about the climate, NWS is an incredible experience at any time of the year. (That's my opinion based on all two times I've subbed here, at least.) This past weekend's concert was rather cheesily titled "The Queen and the Emperor": Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade, and Beethoven's Emperor Concerto. I reaffirmed my affinity to German music, though I'll admit that the second mvt of Scheherazade is good stuff. Love that bassoon! From an experience like this, I always try to take away at least one thing to remember for the rest of my life. Maestro Peter Oundjian did not disappoint. Some interesting thoughts on vibrato: A true vibrato is not about the wiggling of the finger, but the vibrancy of the sound. Oundjian demonstrated to a violinist that even a "senza vib" finger actually vibrates in response to the string. He also demonstrated that a wiggling finger without musical intent behind it sounds no more vibrant than a pure sound. During rehearsals, I experimented with varying magnitudes of vibrato, from lots to "none", but always sympathetically with the strings. I guess I can say that this free trip down to Miami was worth it! I also had a revelation regarding how to survive fridge-less without breaking the bank: peanut butter sandwiches! Bev, I'm looking at you. Sometimes I feel like a puppet. Not in the sense that I'm being controlled, but in that I'm held up by unseen strings. These strings hold me up as I go from practice room to rehearsal to class to concert. They rouse me in the morning, drag me onto the subway at an ungodly hour (rush hour = ungodly for musicians), and keep me at school until I'm done with all that I need to do. I don't notice these strings--until they're suddenly cut.

My friends know that I've had a particularly busy year. I had my first orchestra audition in December, a few concerts in January, my DMA audition in March, and then a whole string of concerts from mid-March to mid-April. In short, those puppet strings have been getting a lot of use this year. And after my New Juilliard concert last Friday, my body crashed. The last time I was sick was almost exactly two years ago--right after taking auditions for Masters programs. (To be specific, I felt illness descending on me within an hour of auditioning at Juilliard, which had been my target for months.) Though I had crossed my fingers against such a thing happening again, I wasn't too surprised when it did hit me. Nor was Nana, who was all ready for this with chicken soup and tea. But I'm finally back up! I'm still sleeping about twice as much as I normally do, but I can afford it right now. I need to regain my strength before the papers, presentations, and finals that culminate in a Master of Music degree from Juilliard! Not that my goodbye will be very teary-eyed, as I'll be returning in the fall for yet another degree. In between the two degree programs will be my summer at Tanglewood as a New Fromm Player! I received the repertoire list, and I've posted the concerts in which I'll be playing on my tanglewood page (a subset of concerts). If you're anywhere near Massachusetts, come check out Tanglewood! There are many different types of concerts going on, nearly at all times of the day! Even if new music isn't your thing, you can swing by for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, or the Tanglewood Music Center Orchestra, or chamber music, or vocal music, or even James Taylor and Yo-yo Ma! I refer to these few days as a "concert binge" because I have more concerts this week than I had for the entirety of first semester! "Binge" having a positive connotation, of course. Concert No. 1 took place yesterday. Daniel Fung and I started off his collaborative recital with the Franck Sonata. Midway through the second movement, I recalled a phrase from class: "heroic flailing". I don't know about heroism in the Allegro movement, but there was definitely some flailing on my part! Overall it was a good performance, but I consider it to be the beginning of a journey, rather than the end. Nana and I have been (somewhat awkwardly) learning the piece with separate collaborative partners; hopefully the two of us will have a chance to record it together later this month!

Concert No. 2 took place earlier today. To close Renate Rohlfing's collaborative recital, Renate, Katharine Dain, Sofia Nowik, and I performed Shostakovich's Seven Romances on Poems by Aleksander Blok. This is a piece that one doesn't hear too often, über unfortunately. Go seek out a performance of this! Or you can keep checking this website and cross your fingers--perhaps the four of us will perform it again soon. I know that I want to! I had to put on several different hats for this piece: a street musician for the third movement, a raging storm for the fifth movement, and a dark, stark, yet supremely emotional chamber musician for movements six and seven. (There weren't enough hats to go around, so I sat out the first, second, and fourth movements.) Closing up this concert binge as Concert No. 3 is my performance with the New Juilliard Ensemble, Friday 4/8 in Alice Tully Hall. The program consists entirely of contemporary Japanese composers. Interestingly, I have never played any Japanese compositions, so Somei Satoh and Karen Tanaka are my introduction to Japanese classical music! Thus I have been having a lot of fun listening to these pieces and trying to understand their language. Though both pieces are what one might call "slow", they feel very different. My one sentence summary of each: Satoh's From the Depths of Silence is what John Cage's 4'33 would sound like if he had actually composed something. Tanaka's Water and Stone is a harmonic interpretation of a murmuring brook. (I realize that most brooks babble--but not this one.) I can't speak about the other pieces on the program, but I wouldn't be surprised if they were quite contrasting to these two pieces. Next week I have no concerts, but I will be trying out contemporary violins. After playing on the Strad a few weeks ago, I realized that I want more than what my instrument can offer. So if anyone has any favorite living luthiers (or a Guadagnini lying around the house) please let me know! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed